It isn't just the video camera that he bought simply because it was on sale. An ardent acquirer of things he doesn't really want or need — such as the fiancé he picked up simply because he didn't want to lose the security blanket of having a girlfriend — Michael is a man whose buyer's remorse includes his whole life.

Far beyond his tentative gait and careful diction, as Michael in Bad Influence, there's a spark of desperation that fills James Spader's eyes from the very first moment he appears onscreen. Delighted and disgusted by chaos in such a way that it's begun eating at his insides, Michael doubles over in pain at the office after he's sabotaged by a coworker jockeying for the same promotion he has his heart set on and his fiance postpones their wedding by a month.

Starting the conversation off by stating she's having second thoughts — as if playing chicken with his true nature — with her seriously long '80s hair weighing her down, Ruth (Marcia Cross) misjudges his look of panic as disappointment and reaffirms her intention to marry the L.A. stock analyst within the year. But it's not the pacification he wants.

Bogged down by WASPish politeness and consumerist yuppie pride, in Michael, we see a man who wants to assert himself but always backs down. Going to a bar to clear his head (if not his stomach), Michael eagerly steps up to play the chivalrous hero for a lovely stranger but the feeling lasts a mere two minutes before his head is pushed down and he finds himself in need of a savior as well.

With the boyfriend of the upset woman Michael bought a drink manhandling the young man and ready to start some static, Rob Lowe's cocksure Alex swoops in and intervenes on his behalf. Not content just to take things right up to the line (the way that the submissive Michael has done all day), Lowe's dominant Alex brandishes a broken beer bottle in his hand, eagerly looking for any excuse to cross it.

Strangers on a beach instead of a train, in Bad Influence, Michael acquires not another object this time but a new magnetic friend in the form of Alex who, like all magnets, attracts as much as we ultimately discover he repels while helping him break bad. Bringing Spader's spark of desperation to the front burner and setting it ablaze like a stick of dynamite, Alex goes from giving Michael advice on how to handle his workplace bully to taking active, radical steps to blow up the unassuming professional's well-ordered life.

Hidden behind one of the charismatic Lowe's megawatt smiles, not to mention a career best performance by the former teen heartthrob, Alex's influence in Influence sends the two into a thrill-seeking life of crime in order to give Michael — at one point hopping up and down like a coked up rabbit on a trampoline — an even greater high.

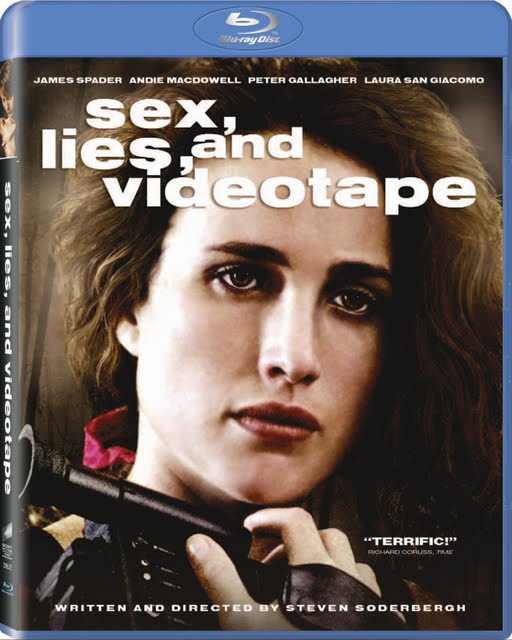

Unfortunately, as his black sheep older brother Pismo (Christian Clemenson) warns, when you get in bed with the devil, "sooner or later you have to fuck." And that's a realization that Michael comes to way too late, and long after he brings home a randy art gallery patron himself and — with Lowe just one floor away — does just that in a thinly veiled moment of Strangers on a Train or Rope like Hitchcockian homoeroticism. Of course, the fact that his conquest involves a videotape given Spader's breakout role in Steven Soderbergh's groundbreaking 1989 indie smash Sex, Lies, and Videotape is a wonderfully meta layer of intertextuality.

Following up director Curtis Hanson's stellar 1987 Rear Window-esque effort The Bedroom Window, which he also wrote, by the time Bad Influence was released, the filmmaker had discovered the perfect genre niche that would serve him well in future hits such as The Hand that Rocks the Cradle, The River Wild, and L.A. Confidential. Hanson's mature yet tongue-in-cheek handling of screenwriter David Koepp's startlingly clever existential allegory of good vs. evil at the start of the 1990s makes Bad Influence the rarest of guilty pleasures. It's a film that's as trashy as it is classy.

Elevated by the sultry, sun-drenched, and shadow filled neo-noir visuals of Paul Thomas Anderson's regular cinematographer Robert Elswit — here in his first of three collaborations with Hanson — as well as the dynamic, fully committed, marquee level turns by its two leads, Bad Influence is a highly compelling adult thriller from the era that churned them out with assembly line efficiency.

Even when Koepp's script pushes things too far towards the terrain of camp as Lowe's character seems to be hosting a game show called "Yuppie Punk'd," the film is filled with some truly masterful sequences that pull us right along. From one scene where Michael discovers that his hand is bloody and doesn't remember why to another where he nervously hides a dead body as a couple (who could discover him at any time) fights nearby, we're right there with the empathetic Spader as we wonder just what it is he might be capable of and what, of course, he might already have done.

Putting us in the dress shoes of our conflicted, morally tested lead, the level to which we hold our breath and try to plot our way out of the men's toxic relationship is a credit to the strength of Koepp's work and foreshadows his future mastering moments like precisely like that in tense thrillers including Jurassic Park and Panic Room.

Daring to subvert audience expectations so that even when we see a game Michael start to make out with a woman at a party, it doesn't appear as though he's fully aroused until he catches Alex from above watching him score, there's a lot going on beneath the surface in a film that could, in other hands, have merely served as fodder for a sleazy Cinemax movie after dark.

A powerful early indicator of the talent involved both in front of and (especially) behind the lens in Hanson, Elswit, and Koepp, Bad remains sophisticated, even when it occasionally succumbs to the basest instincts of a by-the-numbers erotic thriller, including a blink-and-you-missed it denouement.

And while the '90s were a largely hit or miss time for the two leads — particularly Lowe, following his own Sex, Lies, and Videotape scandal at the DNC — it's an absolute treat to see the two desperately try to acquire everything in sight before realizing they're not only desperate but devilishly fucked.

Now Available