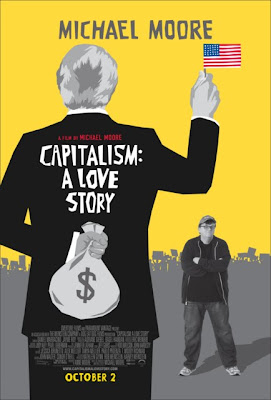

It's easy to say that-- like a majority of esteemed international filmmakers-- Michael Moore's work as a filmmaker has revealed overlapping themes in his twenty year odyssey from trying to get some answers from GM in Roger and Me to analyzing just what exactly is wrong with our corporate driven society in Capitalism: A Love Story.

Yet, the interesting and rather tragic thing about Moore is that everything he was studying in Roger and Me concerning the plant closures and massive layoffs in his hometown of Flint, Michigan on a smaller scale could've served as a warning to the infinitely larger mess in which we now find ourselves.

With an economy at Great Depression lows and so many people losing their homes, jobs and lives to red tape, it's no wonder that Moore tries in vain to make citizen's arrests on Wall Street by attaching crime scene tape to building exteriors and grabbing hold of a megaphone.

Admittedly, some aspects of Capitalism: A Love Story feel like extensions onto his previous acclaimed, award-winning documentaries including not just Roger as we return to Flint a few more times in this one but also Fahrenheit 9/11 and his incredibly devastating examination of the health care system in this country, Sicko. Still overall, Capitalism goes beyond more of the same to take these ideas and show the depths to which people have stooped in the wake of disaster.

The movie opens with a startling comparison of our state of affairs to that of the Roman Empire and a tongue-in-cheek archived 1950s style TV warning that the program we were about to watch was going to be upsetting to pretty much everyone in attendance. Shortly thereafter, Moore asks aloud how the societies of the future will judge us, going right to the old adage of doing just that by illustrating how we treat those less fortunate than ourselves as a family is kicked out of their home.

Giving us a look at the flip-side of capitalism and those who prey on individuals whose hardships have found it impossible to pay off predatory loans, we next encounter a man who runs a company called Condo Vultures, relishing in the bottom feeding aspect of his job of going in like a pirate and stealing the same types of homes we just saw owners thrown out of in another state.

Yet, far from just sharing the cruel things that we do to one another as citizens, Moore goes after his favorite targets including the government and big business to expose corruption, double-talking politicians who bail out banks but do nothing to help their constituents or pretend to loathe the lenders of loans they themselves receive at rates nobody gets.

Naming names all the way from private run juvenile detention centers that used children's well-being as a cash register by imprisoning them for months to over a year for something as immature as throwing a piece of food or two girls getting into a fight at the mall, perhaps the most devastating piece of information that Michael Moore comes across deals with what could in essence be an addendum to Sicko.

Exposing corporations that take out insurance policies on their employees and reap great fiscal rewards upon their death by way of a practice that is actually called “dead peasant insurance” in the industry, the film unravels the complicated web of capitalism to reveal its shadiest and most amoral layers.

Yet this time around, Moore is more careful than he's been in years past. There are no Sicko style trips to Cuba with 9/11 workers in A Love Story because honestly what's going on right here across the country (in what could be considered an entirely new ground zero) is horrifying enough.

And throughout, he covers all of his bases from religion wherein numerous priests interviewed tell the filmmaker who once upon a time actually wanted to be a priest that Jesus would've been opposed to capitalism as a principle. This of course flies in the face of the political religious zealots who've hijacked Jesus as the face of corporate America and turned him into a cheerleader for the rich who steps all over the poor.

And in fact, by taking a more concerted effort to cover as much as he can, Moore certainly does skewer both sides of the political aisle, especially when it comes to the upsetting actions of Senator Chris Dodd and Timothy Geithner. However, given the everything and the kitchen sink approach, the film begins to lose its focus.

As a polarizing cinematic figure, Moore is preaching to Moore's choir and as most of us are more than familiar with his oeuvre, his tendency to repeat the same anecdotes and theses from films of the past and his own personal life aren't just starting to become redundant but they actually take away from the overall impact of this extremely important work.

While it's touching to see Moore's father and meet the various priests who married the filmmaker and other members of his family, Moore should look to colleagues like Robert Greenwald who has the ability to convey an overwhelming amount of facts in a succinct and entirely compelling running time.

Although Moore's style is more accessible and compulsively watchable in his Midwestern, “let me tell you a story,” set-up of always ensuring that time, place, and players are established and proper humor breaks are inserted, Capitalism still feels like it could've had about twenty minutes cut from the finished product without sacrificing the message.

Yet, even with the excess and an itchy remote finger's urge to fast-forward through an overly long strike segment near the end, Capitalism is an all-important wake-up call. Moreover, it's as effective on disc as it was when I first had the opportunity to see it in the theatre on Halloween, correctly assuming it was more horrifying than any fiction that could've been dreamed up by corporate Hollywood.

Referenced and Related

Text ©2010, Film Intuition, LLC; All Rights Reserved. http://www.filmintuition.com

Unauthorized Reproduction or Publication Elsewhere is Strictly Prohibited and in violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

FTC Disclosure: Per standard professional practice, I received a review copy of this title in order to evaluate it for my readers, which had no impact whatsoever on whether or not it received a favorable or unfavorable critique.