Bookmark this on Delicious

Print Page

While I'll never be able to recall all of the bizarre information I crammed into my brain to try and ace tests in college, to this date there are still two distinct queries from academic exams that I know I will never forget. The questions were posed in two very different courses at two very different institutions of higher learning geographically located in opposite sides of the country from two very different instructors. Yet the most important thing that the inquiries had in common was that the answer necessitated us to create a seemingly impossible definition for two very different terms—namely the concepts of “normal” and “art.”

While it’s easy to throw around phrases like “that’s not normal” in judging another person's behavior or ridiculing objects in museums as the opposite of “art,” when you get right down to actually defining what both of those ideas mean, it’s nearly impossible to do so in a way that would go beyond the most basic dictionary terminology. Yet, both of these questions plague us on a daily basis as we go about our lives whether we face someone whose actions we’re unable to understand on the evening news or when assessing the moral and ethical implications surrounding art that we judge without even realizing it.

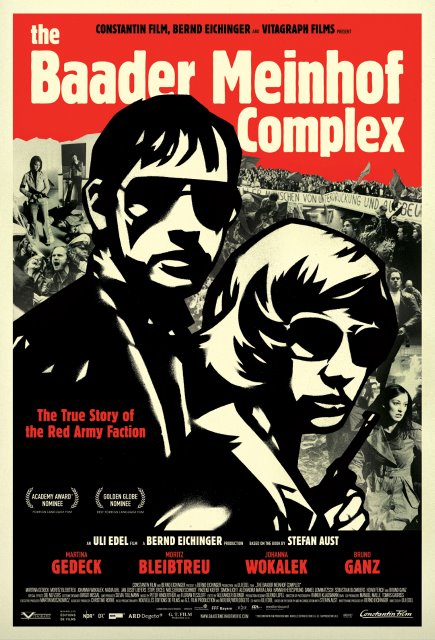

However, for audience members taking in Uli Edel’s Oscar nominated film The Baader Meinhof Complex as it opens in limited release on 8/21 before expanding nationwide—it’s precisely these two questions, either combined or separately that will haunt you both while the 150 minute work plays and after the final credits roll.

Obviously anytime a person takes the step from creating something to then sharing it with others (one possible definition of art), they open themselves up for the harshest of criticism and this is especially true for filmmakers. However, it’s all the more controversial if you’re making a historical work about terrorists from the point-of-view of the terrorists. And such is the case for Edel’s endlessly complicated, morally and ethically loaded, and naturally provocative Complex.

Edel’s movie was one of the five nominated global works that was selected for inclusion in the Academy Awards’ Best Foreign Film Category. And although Japan’s Departures ended up taking the statue—similar to the brave and politically charged yet superior Waltz With Bashir-- Germany’s startling and controversial submission uses subject matter that hasn’t been fully explored in the United States aside from Stefan Aust’s definitive nonfiction book which was used as the film’s source.

To be fair, however initially I felt that Edel’s film that chronicled a decade of tumultuous anarchic revolution by the group dubbed Red Army Faction from 1967 to what was deemed “The German Autumn” of 1977 was perhaps new terrain only to those of us who were part of Generation X or Y. Yet much to my surprise, when I shared the screener with a Baby Boomer, they too were completely blown away by the lack of coverage in the States about the events being depicted onscreen. Although, contrary to the popular image of flower power, Woodstock, astronauts, and disco, when you honestly do a reality check you become acutely aware that the whole world essentially went mad during the Vietnam era as several countries became politically unstable with revolutions, rallies, protests and assassinations including the United States.

And when you couple this with the fact that Red Army Faction was originally organized to combat our policy with in Vietnam as members felt that “American imperialism supported by the German establishment, many of whom have a Nazi past,” was “the new face of fascism,” understandably you get that it is a topic that is still explosive enough to send shock waves around the globe.

And while it’s extremely illuminating from a historical point-of-view, the biggest folly for Baader is in its grand ambition in trying to explain the history of RAF in one work. However, when the bloated film threatens to lose us via its sheer length and a presentation where too much guesswork is being done on our part when we long for facts, overall it’s buoyed by the strength of its leads as well as the attention paid to authenticity from every department.

Similarly the film works best when it centers on its main trio. Namely, this consists of the middle class, highly regarded journalist Ulrike Meinhof (Martina Gedeck) who leaves her unfaithful husband and later ultimately puts the cause before her children as well in joining up with the leftist group headed up by Andreas Baader (Moritz Bleibtreu) and his significant other Gudrun Ensslin (Johanna Wokalek).

Obviously, given the cause of their anger directed at Germany's alliance with America, it makes our country's interest in The Baader Meinhof Complex especially uncertain being that the picture is releasing during a time of dual wars and more debate over our dependence on foreign oil which is addressed in the movie. Additionally, although it’s a historically accurate film, the movie has also been frequently charged with not only confusing its viewers throughout but also to some extent in treating the terrorists as folk heroes.

And while it’s easy to jump to that conclusion because the terrorists have the most screen time, overall I don’t believe that it was the intention of the director to glorify the individuals represented. For, ultimately Edel succeeds in illustrating the futility of violence as the original ideas and motives of the group are cast aside in favor of horrific violence which led to the infamous RAF hijacking (along with Middle Eastern allies) of the Lufthansa airplane which no one can view as a positive or normal.

However, shockingly in the film we do learn that earlier on in their movement, one in four German citizens sympathized with the cause to the tune of 10,000 individuals being classified as such by the government. Although, watching it today in post-9/11 America, nothing presented in the movie can be seen as glamorous in my eyes since when ideas are replaced with bullets, all credibility is gone but then again that's another debate about what constitutes our ideas of art and normal behavior.

However, on the other hand I can definitely understand the charge being leveled at the picture. For, in the second half of the movie as the group moves from ideas into extremely violent territory with escalating crimes and murders, unfortunately most of the characters involved are simply painted in the broadest of strokes as the details become sketchy.

To this end, I wholeheartedly empathize with those who suffered from the experience including one widow who has filed suit against the movie because her husband’s murder is featured onscreen in a way she felt trivialized his death. Thus, again this brings the question of what is art back into the puzzle. And while this has to be a traumatic experience to relive regardless, I believe it’s even worse when murders presented in the film are merely used in a fast-paced action style wherein the deaths and killers are poorly defined.

Most likely the fault for our lack of understanding the reasoning behind the repetitions of violence and who the players were in the crimes is due to the screenplay. By trying to truncate a decade of material into one film and without the aid of perhaps inserting cards to state who is who or where we are-- ultimately we end up shortchanged and without the benefit of knowledge or understanding that will last-- much like a kid cramming for an exam.

While my reaction to it overall is mixed because the viewer is left in the dark far too often, it’s still a vital and valid offering to view a work that reveals yet another side of the ‘70s which I’d never experienced before. And likewise as a feature film, it’s one that’s all the more impressive since it’s so extremely well made by its talented cast and crew that it looks and sounds as though it was a lost German film from that particular era just resurfacing today.

Text ©2009, Film Intuition, LLC; All Rights Reserved. http://www.filmintuition.com

Unauthorized Reproduction or Publication Elsewhere is Strictly Prohibited.