Read Film Intuition's Interview With Jeremy Renner

Movie Still Slideshow

Now Available to Own

The way that Anthony Mackie describes his character Sergeant J.T. Sanborn in the film The Hurt Locker is that-- given his “seven years in intelligence before joining EOD [Explosive Ordinance Disposal a.k.a. the Bomb Squad]-- he’s a smart, capable, reliable, [and] charismatic guy.” But nonetheless as the “film’s Everyman,” he is likewise one, “who has never encountered a whirlwind like [actor Jeremy Renner’s character] James before.”

Of course, neither has the audience and it’s likely that both the character of Renner’s Sergeant William James and the actor playing him is one we won’t soon forget. James is an individual-- as I had the sheer pleasure to personally tell Renner-- that's not just a role but one of those great and unspeakably rare Cool Hand Luke parts blended along with what I can only call the mischievous “Kubrick face” of madness and joy.

And he is brought into the film after its harrowing roughly eight minute opener that finds a major movie star and the leader of the EOD’s three man unit dead in a chilling sequence that puts the viewers on the ground with the soldiers. Following the introduction where dialogue is necessarily minimal given the danger of the Iraqi “kill zone," Renner’s Sergeant William James is given a perfunctory introduction when he tells Sanborn that he won’t try to fill the deceased’s shoes but just do the best he can.

However, his “big moment,” comes when the trio (also consisting of the film’s “heart” in the form of Brian Geraghty’s Eldridge whom director Kathryn Bigelow described as “every mother’s son”) go out on their first routine op. More specifically it occurs when Sanborn and Eldridge test his mettle in the hummer on the way there, noting that “pretty much the bottom line is if you’re in Iraq, you’re dead.” Of course, this is before we discover that James had not only been previously in Afghanistan but has also dismantled 873 bombs before he joined their team.

Instead of allowing his second-in-command Sanborn to talk him into sending a “bot” or remote control wagon down to investigate the possible danger, James just goes right down at it like a Wild West cowboy, breaking protocol the first of many times throughout when he uses a smoke canister to create a diversion. Additionally, as opposed to just taking cover, he stands calmly in the middle of the street when an Iraqi cabbie drives full speed past the screaming soldiers, stopping just short of plowing down James.

Drawing out his pistol, firing warning shots first near the car and then through the windshield until he rests the gun solely on the man’s forehead—again without backup until the guy finally does back up, James coolly deadpans into his mic, “well, if he wasn’t an insurgent, he sure the hell is now.”

This is all foreplay of course, before he proceeds to just get right down on the ground like a kid playing in a sandbox, stroking the bombs with fetishistic pleasure, appreciating the artistry so much that he keeps the parts of some of the things that almost kill him (along with his wedding ring and a photo of his son) under his bed.

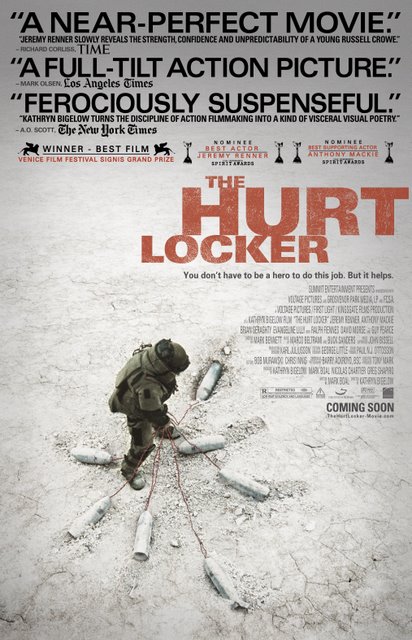

Taking care of the threat and informing Sanborn that “we’re good to go”—soon, just like the way the opening of the film suddenly changed in an instant with the previously unseen bystander who evolved into “dude’s got a phone,” James finds another wire that leads him to an endless string of IEDs that became the film’s incredibly eerie poster image.

While he handles that threat, sure enough we do see another “dude with a phone” make a break for it out of his eye-line. And in what is easily the best film of the year so far and the best war film I’ve seen in several years—this is just one of countless obstacles, explosions, gunfire, and complications that the trio’s Bravo company experiences in Bigelow’s fittingly “experiential” film during the 38 days they have left in rotation before they can finally return home.

Still, the fact that remains—although nothing detonated that day (and in fact the title comes from the soldiers’ own description of Mark Boal’s time spent with a special bomb unit who described the impact of explosions as putting yourself “in the hurt locker” as the production notes reveal), Sergeant James’s handling of the situation is anything but by-the-book and it becomes a bone of contention between him and Sanborn.

Essentially the personification of the quote that opens the film that “war is a drug"-- James is one of the most psychologically fascinating characters to be found in a war film since Platoon, Full Metal Jacket, and Apocalypse Now (incidentally three films Bigelow cites throughout Nick Dawson’s must-read article in Filmmaker Magazine’s Spring 2009 issue).

And this is all the more confounding because you can’t write him off as a simple thrill junkie, nor as Mackie angrily charges after a dangerous display of swaggering bravado “a redneck piece of trailer trash,” since he does what very few people in the world would be able to do. Yet he dismisses it to a falling-all-over-himself complimentary superior (David Morse) as attempting to do so “the way you don’t die, sir.”

As a former Ranger with such an impressive record of doing it “the way you don’t die," James also in another dynamite sequence throws not only his 100 pound suit off but his headset and link to Sanborn in order to concentrate on a highly elaborate bomb wired into a car at a UN building—having decided that if he’s going to die, he’ll at least "die comfortably" and without the excess gear. And in moments such as these, you’re able to understand the psyche the job requires. For because the soldiers have developed split second, flip a switch, left or right, yes or no decisions--when they’re away from the kill zone, they’re never fully at ease or able to feel that desperately alive at-- say-- the grocery store.

Yet it's all part of the daily routine working in a field that originated in World War II which found US and British soldiers collaborating in tandem to make pencil diagrams of time-delayed explosive devices which they tried to dismantle with commonplace tools. And in Locker, Bigelow and the journalist turned screenwriter Mark Boal-- who also turned his experiences into another psychological exploration of after-effects with the Tommy Lee Jones' Oscar nominated effort In the Valley of Elah-- educate us about what it takes to walk towards bombs when everyone else walks away.

As I discovered in the thorough and informative notes provided by Summit Entertainment—EOD soldiers are so rare, specialized, and in such a dangerous field that the technicians were not only “five times more likely to die than all other soldiers” and relationship difficulties are so mainstream that an in-joke is that EOD also means “every one divorced” but “the insurgency reportedly placed a $25,000 bounty on the heads of EOD techs.”

Of course, while stateside citizens dial 911 to report suspicious activity—whenever military personnel is both unfortunate enough to find an insurgent-made IED yet fortunate enough not to be one of the casualties from the opposition’s deadliest weapon of choice, EOD takes the call. And as Mark Boal notes, “sometimes [this occurs up to] 10 or 20 times a day… and the bomb squad has to deal with it while everyone else in the military pulls back.”

“The fact that these men live in mortal danger every day make their lives inherently tense, iconic and cinematic and on a metaphorical level, they seemed to suggest both the heroism and the futility of the war,” as Bigelow explains. And by using her trademark multiple camera set-up and visual arts background (Point Break, Strange Days) to keep the actors on their toes in long takes with 4 cameras constantly moving and out of sight-- like the ninjas that Renner likened them to since he never knew where they were during the 44 day shoot in Jordan-- Bigelow brings the audience into the EOD unit.

Easily described as a docudrama but also one that Boal likened to naturalism or “true fiction,” by avoiding trendy rapid video-game style cuts or abrupt changes in orientation since Bigelow proves her belief from the powerful beginning that “it’s really important to never let the audience lose a sense of geography,” she takes great pains to “draw them further and further into this vortex of information,” (Filmmaker, pg. 37).

And this is precisely why the film was honored with the SIGNIS and Human Rights Film Award at the Venice Film Festival since as they noted it “avoids dry ideology” and offers “an uncompromising approach to the Iraq war and its consequences seen through the experience [of the EOD]…for whom war is an addiction rather than a cause." And by doing so, “Kathryn Bigelow challenges the audiences view of war in general and the current war in particular [by] demonstrating the struggle between violence to the body and psychological alienation.”

So instead of an overt message movie, Bigelow was more fascinated by telling a simple and engrossing story about the war from the point-of-view of a handful of soldiers we come to know much better than in traditional war pictures where we can only tell them apart because of the names on their helmets or the high profile actors playing them because this time we’re in it completely along with them.

For, as she told Filmmaker’s Nick Dawson, “literature can be reflective, but film can be experiential,” and she loves it when both the mediums of photography (which was given a powerful boost by the amazingly gifted Bourne Supremacy, Bourne Ultimatum, and United 93 cinematographer Barry Ackroyd) and cinema can do just that as, “the gift of traveling you from [here] to… wherever” is what drives her (37).

Although The Hurt Locker had the misfortune of following the box office disasters of countless Iraq-themed pictures which made funding and distribution an incredible uphill climb for Bigelow and those involved, additionally it gave her unprecedented creative freedom of not being tied to “yes men” or studio execs. And the film, which marks the director’s return to feature filmmaking for the first time since 2002's K-19: The Widowmaker is the best example of her own unique brand of experiential moviemaking and moreover, her strongest work so far.

Yet throughout the process of planning the film out so precisely that “the directing, script, camera work, music, editing—was conceived from the beginning with the single goal of creating that heightened sense of realism that underscores the tension,” she’s completely correct in stating that ultimately the film doesn’t allow itself to be too “cinematic” so that it takes away from the complexities of the characters.

I, for one have not been able to stop thinking about the soldiers of Locker for weeks. Moreover I believe that not only will it stay ingrained in your memory long after the movie ends but it will haunt you the way that excellent cinema should by going off the screen and into your life, filling the air of your conversations with others as you realize that similar to Mackie’s warning-- nothing has ever prepared you “for a whirlwind like” Renner’s James or The Hurt Locker style of genre-busting war film before.

Of course, neither has the audience and it’s likely that both the character of Renner’s Sergeant William James and the actor playing him is one we won’t soon forget. James is an individual-- as I had the sheer pleasure to personally tell Renner-- that's not just a role but one of those great and unspeakably rare Cool Hand Luke parts blended along with what I can only call the mischievous “Kubrick face” of madness and joy.

And he is brought into the film after its harrowing roughly eight minute opener that finds a major movie star and the leader of the EOD’s three man unit dead in a chilling sequence that puts the viewers on the ground with the soldiers. Following the introduction where dialogue is necessarily minimal given the danger of the Iraqi “kill zone," Renner’s Sergeant William James is given a perfunctory introduction when he tells Sanborn that he won’t try to fill the deceased’s shoes but just do the best he can.

However, his “big moment,” comes when the trio (also consisting of the film’s “heart” in the form of Brian Geraghty’s Eldridge whom director Kathryn Bigelow described as “every mother’s son”) go out on their first routine op. More specifically it occurs when Sanborn and Eldridge test his mettle in the hummer on the way there, noting that “pretty much the bottom line is if you’re in Iraq, you’re dead.” Of course, this is before we discover that James had not only been previously in Afghanistan but has also dismantled 873 bombs before he joined their team.

Instead of allowing his second-in-command Sanborn to talk him into sending a “bot” or remote control wagon down to investigate the possible danger, James just goes right down at it like a Wild West cowboy, breaking protocol the first of many times throughout when he uses a smoke canister to create a diversion. Additionally, as opposed to just taking cover, he stands calmly in the middle of the street when an Iraqi cabbie drives full speed past the screaming soldiers, stopping just short of plowing down James.

Drawing out his pistol, firing warning shots first near the car and then through the windshield until he rests the gun solely on the man’s forehead—again without backup until the guy finally does back up, James coolly deadpans into his mic, “well, if he wasn’t an insurgent, he sure the hell is now.”

This is all foreplay of course, before he proceeds to just get right down on the ground like a kid playing in a sandbox, stroking the bombs with fetishistic pleasure, appreciating the artistry so much that he keeps the parts of some of the things that almost kill him (along with his wedding ring and a photo of his son) under his bed.

Taking care of the threat and informing Sanborn that “we’re good to go”—soon, just like the way the opening of the film suddenly changed in an instant with the previously unseen bystander who evolved into “dude’s got a phone,” James finds another wire that leads him to an endless string of IEDs that became the film’s incredibly eerie poster image.

While he handles that threat, sure enough we do see another “dude with a phone” make a break for it out of his eye-line. And in what is easily the best film of the year so far and the best war film I’ve seen in several years—this is just one of countless obstacles, explosions, gunfire, and complications that the trio’s Bravo company experiences in Bigelow’s fittingly “experiential” film during the 38 days they have left in rotation before they can finally return home.

Still, the fact that remains—although nothing detonated that day (and in fact the title comes from the soldiers’ own description of Mark Boal’s time spent with a special bomb unit who described the impact of explosions as putting yourself “in the hurt locker” as the production notes reveal), Sergeant James’s handling of the situation is anything but by-the-book and it becomes a bone of contention between him and Sanborn.

Essentially the personification of the quote that opens the film that “war is a drug"-- James is one of the most psychologically fascinating characters to be found in a war film since Platoon, Full Metal Jacket, and Apocalypse Now (incidentally three films Bigelow cites throughout Nick Dawson’s must-read article in Filmmaker Magazine’s Spring 2009 issue).

And this is all the more confounding because you can’t write him off as a simple thrill junkie, nor as Mackie angrily charges after a dangerous display of swaggering bravado “a redneck piece of trailer trash,” since he does what very few people in the world would be able to do. Yet he dismisses it to a falling-all-over-himself complimentary superior (David Morse) as attempting to do so “the way you don’t die, sir.”

As a former Ranger with such an impressive record of doing it “the way you don’t die," James also in another dynamite sequence throws not only his 100 pound suit off but his headset and link to Sanborn in order to concentrate on a highly elaborate bomb wired into a car at a UN building—having decided that if he’s going to die, he’ll at least "die comfortably" and without the excess gear. And in moments such as these, you’re able to understand the psyche the job requires. For because the soldiers have developed split second, flip a switch, left or right, yes or no decisions--when they’re away from the kill zone, they’re never fully at ease or able to feel that desperately alive at-- say-- the grocery store.

Yet it's all part of the daily routine working in a field that originated in World War II which found US and British soldiers collaborating in tandem to make pencil diagrams of time-delayed explosive devices which they tried to dismantle with commonplace tools. And in Locker, Bigelow and the journalist turned screenwriter Mark Boal-- who also turned his experiences into another psychological exploration of after-effects with the Tommy Lee Jones' Oscar nominated effort In the Valley of Elah-- educate us about what it takes to walk towards bombs when everyone else walks away.

As I discovered in the thorough and informative notes provided by Summit Entertainment—EOD soldiers are so rare, specialized, and in such a dangerous field that the technicians were not only “five times more likely to die than all other soldiers” and relationship difficulties are so mainstream that an in-joke is that EOD also means “every one divorced” but “the insurgency reportedly placed a $25,000 bounty on the heads of EOD techs.”

Of course, while stateside citizens dial 911 to report suspicious activity—whenever military personnel is both unfortunate enough to find an insurgent-made IED yet fortunate enough not to be one of the casualties from the opposition’s deadliest weapon of choice, EOD takes the call. And as Mark Boal notes, “sometimes [this occurs up to] 10 or 20 times a day… and the bomb squad has to deal with it while everyone else in the military pulls back.”

“The fact that these men live in mortal danger every day make their lives inherently tense, iconic and cinematic and on a metaphorical level, they seemed to suggest both the heroism and the futility of the war,” as Bigelow explains. And by using her trademark multiple camera set-up and visual arts background (Point Break, Strange Days) to keep the actors on their toes in long takes with 4 cameras constantly moving and out of sight-- like the ninjas that Renner likened them to since he never knew where they were during the 44 day shoot in Jordan-- Bigelow brings the audience into the EOD unit.

Easily described as a docudrama but also one that Boal likened to naturalism or “true fiction,” by avoiding trendy rapid video-game style cuts or abrupt changes in orientation since Bigelow proves her belief from the powerful beginning that “it’s really important to never let the audience lose a sense of geography,” she takes great pains to “draw them further and further into this vortex of information,” (Filmmaker, pg. 37).

And this is precisely why the film was honored with the SIGNIS and Human Rights Film Award at the Venice Film Festival since as they noted it “avoids dry ideology” and offers “an uncompromising approach to the Iraq war and its consequences seen through the experience [of the EOD]…for whom war is an addiction rather than a cause." And by doing so, “Kathryn Bigelow challenges the audiences view of war in general and the current war in particular [by] demonstrating the struggle between violence to the body and psychological alienation.”

So instead of an overt message movie, Bigelow was more fascinated by telling a simple and engrossing story about the war from the point-of-view of a handful of soldiers we come to know much better than in traditional war pictures where we can only tell them apart because of the names on their helmets or the high profile actors playing them because this time we’re in it completely along with them.

For, as she told Filmmaker’s Nick Dawson, “literature can be reflective, but film can be experiential,” and she loves it when both the mediums of photography (which was given a powerful boost by the amazingly gifted Bourne Supremacy, Bourne Ultimatum, and United 93 cinematographer Barry Ackroyd) and cinema can do just that as, “the gift of traveling you from [here] to… wherever” is what drives her (37).

Although The Hurt Locker had the misfortune of following the box office disasters of countless Iraq-themed pictures which made funding and distribution an incredible uphill climb for Bigelow and those involved, additionally it gave her unprecedented creative freedom of not being tied to “yes men” or studio execs. And the film, which marks the director’s return to feature filmmaking for the first time since 2002's K-19: The Widowmaker is the best example of her own unique brand of experiential moviemaking and moreover, her strongest work so far.

Yet throughout the process of planning the film out so precisely that “the directing, script, camera work, music, editing—was conceived from the beginning with the single goal of creating that heightened sense of realism that underscores the tension,” she’s completely correct in stating that ultimately the film doesn’t allow itself to be too “cinematic” so that it takes away from the complexities of the characters.

I, for one have not been able to stop thinking about the soldiers of Locker for weeks. Moreover I believe that not only will it stay ingrained in your memory long after the movie ends but it will haunt you the way that excellent cinema should by going off the screen and into your life, filling the air of your conversations with others as you realize that similar to Mackie’s warning-- nothing has ever prepared you “for a whirlwind like” Renner’s James or The Hurt Locker style of genre-busting war film before.

Unauthorized Reproduction or Publication Elsewhere is Strictly Prohibited.