Now Available to Own

Film Information

(Each Volume Contains 4 Films on 2 Discs)

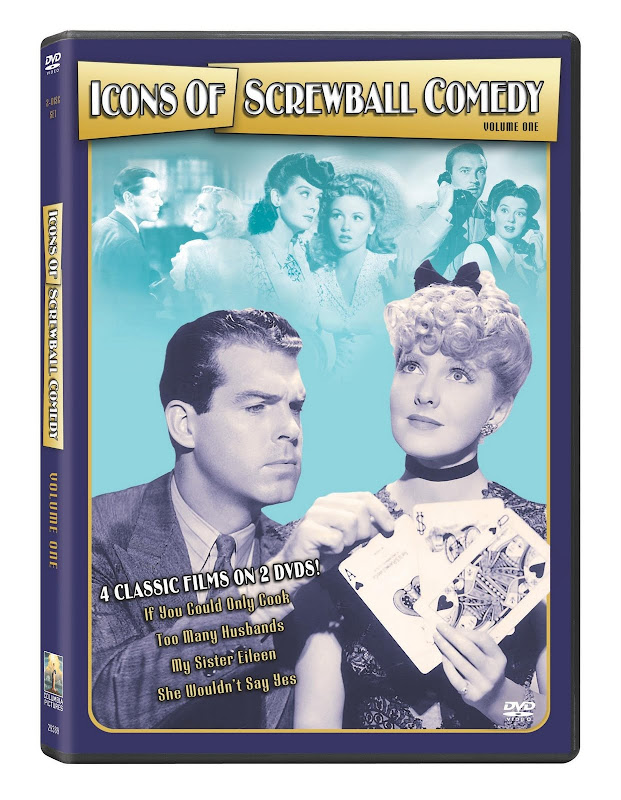

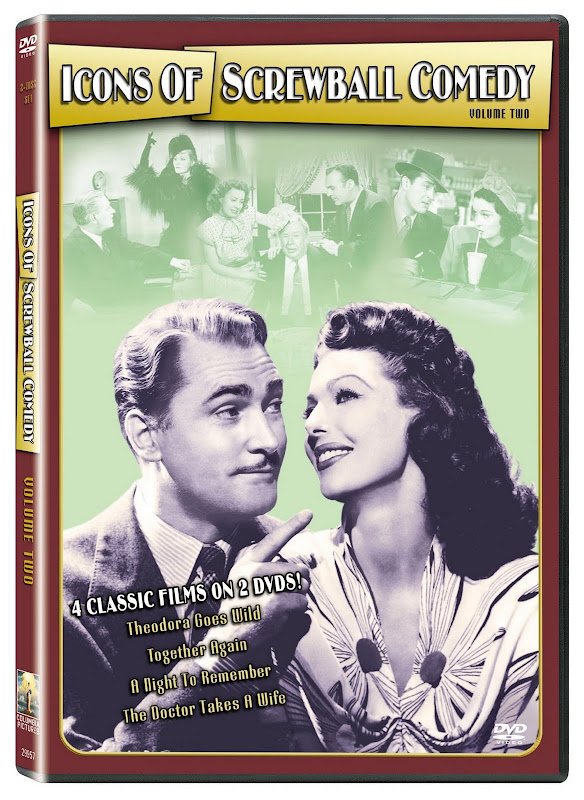

Volume 1: If You Could Only Cook (1935); Too Many Husbands (1940); My Sister Eileen (1942); She Wouldn't Say Yes (1945)Volume 2: Theodora Goes Wild (1936); Together Again (1944); The Doctor Takes a Wife (1940); A Night to Remember (1943)

Just like Monty Python, The Three Stooges, Cirque du Soleil, the game of golf and cats, screwball comedy isn't for everyone. You have to be the type of individual who's first and foremost unafraid of black and white movies which sadly has become a rare thing indeed as I was shocked to engage in a recent conversation with my grandmother wherein she confessed that-- having recently made the switch to HD television and DVD-- she no longer has any desire to watch black and white movies.

So last week, while my eighty-something grandparents were watching Liam Neeson fly to Paris to hunt down the sex-traffickers who abducted his daughter in the brilliant action movie Taken in crystal clear HD, I snuggled up to some vintage Columbia black and white classics from the '30s and '40s. And in so doing, I reveled in the romantic misadventures of fast-talking dames, the helpless fellas who struggled to keep up, and the wackiest plots that Hollywood screenwriters could crank out during that one, unforgettable golden age.

The works are often based on theatrical or literary source material-- whether adapted from a stage play, short story or novel but they are given that uniquely identifiable screwball spin. The films largely consist of the following: rapid-fire dialogue, mixed messages, only-in-the-movies coincidences, improbable set-ups, characters who fail to be talking about the same thing at the same time and they can't be persuaded otherwise, and enough eccentric supporting characters to fill a psychoanalyst's couch for a full year. And when writers put all of these ingredients together, audiences were in for some of the wittiest comedies produced in the romantic comedy genre.

Finally giving women roles that were on par with the male leads-- Columbia Pictures (now under the arm of Sony) was at the forefront of the trend. And beginning in the '30s, they released movies that still hold up today such as Frank Capra's incomparable It Happened One Night, which is the Best Picture winner that arguably started the screwball craze.

While the screwball effect still shows up every so often today (rent the indie charmer Ira & Abby for example), it flourished during the era of the Great Depression and World War II when audiences needed to see something completely different than their daily lives.

Offering viewers escapist works that ridiculed the elite upper classes in movies like My Man Godfrey, Holiday, The Philadelphia Story, Bringing Up Baby or letting the screwball format meander into mysteries in The Thin Man series-- one of its most celebrated achievements was for the ingeniously freewheeling Howard Hawks picture His Girl Friday.

As women began to join the workforce, Hawks' brisk newspaper comedy broke new ground by casting Rosalind Russell opposite Cary Grant in a part that had been played by a man that is likewise famous for shooting two pages from the script in one minute which is double the norm and explains why there's so much natural overlap and fast-paced speech in the movie.

While all of the aforementioned films have always been easily accessible, many have been remastered, become available on Blu-ray and given the deluxe treatment in the form of study regarding their content and history-- so many wonderful movies have been lost in the archives during the prolific studio years.

Although Warner Brothers has begun opening up their archives recently as well for low-priced downloads and releases along with premiering some gorgeous box sets earlier in the year for stars like Natalie Wood, Sidney Poitier, Doris Day, etc., Sony Pictures Home Entertainment-- which unveiled one of the finest collections of 2009 with their Jack Lemmon box set of films that had never been offered to fans in any format before-- is back with two volumes of forgotten screwball classics.

Boasting four films in each two-disc set, the titles feature such legendary Oscar winners and nominees that are synonymous with the genre and era including Rosalind Russell and Irene Dunne-- both of whom are starring in films that garnered them nominations. Along with these two, the films also star Jean Arthur, Fred MacMurray, Melvyn Douglas, Loretta Young, Charles Coburn and countless others in eight titles that are lovingly included along with classic shorts and original theatrical trailers.

And although they compliment each other nicely, conveniently Sony took great care to ensure that fans of certain entertainers woul be able to choose one volume over the other if they so decided as the first volume opens with a Jean Arthur double feature a la If You Could Only Cook and Too Many Husbands on disc one before Rosalind Russell keeps the laughs coming on the second disc with My Sister Eileen (for which Russell received an Oscar nomination in a role she would later play again in Broadway musical form) and She Wouldn't Say Yes.

Likewise, the second volume's first double feature centers on the irreplaceable Irene Dunne in her first breakthrough starring role via Theodora Goes Wild (which garnered her an Academy Award nomination) and Together Again before the likable Loretta Young concludes the set with The Doctor Takes a Wife and A Night to Remember.

While as a writer, I was especially enchanted with the three of the four works about writers-- including Eileen, Theodora, and Doctor-- it was Eileen that was the strongest of them all and it's no surprise that it initially originated first as a New Yorker piece before becoming a play, then the film, later a stage musical renamed Wonderful Town, until more remakes ensued.

The film centers on two Ohio sisters played by Rosalind Russell and Janet Blair who leave their community in disgrace after newspaper scribe Russell writes a rave review of her sister's theatrical debut before the show goes on only for the daughter of her boss to be put under the spotlight. When they decide to head to New York for success in print and on the stage, they discover the wild side of Greenwich Village life when they get suckered into renting a basement room that's busier than Grand Central Station. To this end, a bizarre cast of neighborhood characters and admirers of Eileen parade throughout, undaunted by the eighteen hour a day surprise explosions of a local construction crew building a subway nearby.

While most writers would be scrambling for any quiet location they could find, the chaos and the community become her muse in a film that-- at its heart-- recalled Capra's You Can't Take it With You, Cukor's Holiday, and the type of lineup you'd find in a movie by Ernst Lubitsch or Preston Sturges.

While the second half of the Rosalind Russell double-feature is also very entertaining-- yet not in the league of Eileen-- She Wouldn't Say Yes is similar in the same sense that it goes on for one act too many as it begins with a very relatable and intriguing opposites attract storyline and then pushes it a bit too far into a strange wedding plot that feels a bit tacked on.

Still, until then, it's good fun to see Russell as a no-nonsense professional psychiatrist who, having worked with soldiers suffering from stress and shell-shock upon their return from war, meets her match when she encounters a GI cartoonist (played by Lee Bowman) who encourages people to follow their Freudian id and act on their impulses.

As his impulse is to prove her wrong and to marry her before his work takes him overseas for military service, he schemes along with Russell's father in this light but mostly enjoyable comedy that reunited the actress with her Eileen director Alexander Hall. While the ending of Yes feels like it was the result of too many rewrites and makes Russell's double-feature uneven-- frequent Frank Capra leading lady Jean Arthur's opening duo of films are wholeheartedly entertaining works and true gems.

Indicative of My Man Godfrey and My Favorite Wife respectively, Arthur initially meets cute with a man whom she assumes is equally down on his luck and unemployed in If You Can Only Cook when a stranger (Herbert Marshall) sits down next to her on a park bench. Not realizing that he's actually the head of an automobile company who's designed cars she truly admires, Arthur unknowingly peruses the want-ads with him and suggests that he join her and pose as her husband so they can get hired as a cook and butler respectively.

Drawn by her ingenuity and that Arthur twinkle in her eye and adorable voice, he decides to help the young woman out and they gain employment working for a mobster at his mansion. But when they learn they're supposed to share a room and he has yet to confess not just his identity but the fact that he's engaged and he soon starts to develop feelings for Arthur, things get hilariously complicated.

In Too Many Husbands, it's Arthur's turn to find herself torn between romantic prospects when she realizes that the husband she'd assumed was deceased (Fred MacMurray) returns unexpectedly only to realize that his arrival has made Arthur a bigamist since she'd married his best friend (Melvyn Douglas) while he'd been away. While first tempers flare, when Arthur informs them that anger is never the right way to win a woman's heart, the games of wooing begin in this delightful charmer based on the play by W. Somerset Maugham.

With the first volume being so successful and witty, the bar had been raised very high by the time I began the second set released last week from Sony Pictures but I felt quite optimistic that our initial leading lady was Irene Dunne who had starred in one of my favorites of the era opposite Cary Grant in The Awful Truth (among others).

In the second "writer movie" contained in the volumes, we witness Dunne in her first legitimate star vehicle Theodora Goes Wild as a buttoned up, church going virginal small town girl who writes salacious bestsellers under a pseudonym to avoid scandalizing her family and friends.

Challenged about her prudish nature by the seductive artist (Melvyn Douglas), Dunne plays right along by trying to act like one of her heroines until eventually she runs out of his bachelor pad and is shocked when he follows her to her small town. However, instead of unmasking her in front of others, Dunne realizes that perhaps who she really is may be a cross between the woman on the pages and the spinster she pretends she is in her small town. Yet cleverly, the film delivers numerous twists that avoid us from guessing exactly where it's headed when we're startled to learn the truth about Douglas as well.

Released in 1936 and censored due to some of the suggestive situations and ideas the film puts forth about matrimony and male and female roles which make its Oscar nomination for Best Editing especially ironic-- refreshingly, this release from Columbia has been both restored and uncut for its DVD debut in the set.

However, I was less thrilled with the next Dunne selection of Together Again. Yet, perhaps it is most notable for marking the occasion of the first comedic collaboration of popular onscreeen couple Dunne and Charles Boyer after Love Affair (later remade as An Affair to Remember) and When Tomorrow Comes-- Theodora finds a great companion movie with the Loretta Young vehicle The Doctor Takes a Wife.

Much like the Doris Day and Rock Hudson movies, you can go ahead and cite this film as perhaps having been an inspiration on the clever and underrated Down With Love as it finds Young's nonfiction scribe famous for penning a work called "Spinsters Aren't Spinach." After Young forces her way into getting a ride home with neuropsychiatrist Ray Milland from Massachusetts to New York City and a child mistakenly attaches a "Just Married" sign onto their vehicle, suddenly the spokeswoman for single women who enjoy living alone is called a hypocrite.

So in order to spin this to her favor, save her book career and no doubt get another book out of the situation by writing a sequel about marriage, Young's publisher persuades both Young and Milland to go along with the ruse since it enhances his career as well when he's granted a professorship and can finally wed the real woman of his dreams.

Agreeing to keep up the pretense that they're married until they can feign a divorce when Young's sequel to "Spinsters" hits the shelves and climbs the bestseller charts-- predictably things get complicated when more people are let in on the situation, other feelings are hurt and Milland and Young realize that maybe this fake marriage is better than most real relationships they'd had before.

Setting the second Young film in Greenwich Village which was also the same neighborhood utilized for the pre-Beatnik era My Sister Eileen, we're offered A Night to Remember. A lackluster thriller comedy, this marks the fourth and final writer movie where this time where Young's husband played by Brian Aherne is the scribe.

Not nearly as successful as the movies about the witty female writers even when Young tries to persuade her husband to write a love story-- the movie moves uneasily between comedy and thriller which wouldn't be put together with quite the right ingredients until Cary Grant was cast alongside some sweet but deadly old ladies in Arsenic and Old Lace just one year later.

While despite the fact that the first volume comes wholeheartedly recommended, the outcome of its follow-up can be divided in half with simply Theodora Goes Wild and The Doctor Takes a Wife-- which thematically and structurally would've worked as a marvelous double feature-- being the only ones worth a repeat play.

However, similar to the Paramount Centennial Collection which as a film geek I've been ritually hanging onto for the quality and fact that some of these movie are just so rare, I can definitely understand the importance for devotees of the genre to get both. Although, if you're new to screwball or if your budget is tight, you may want to simply go with the first set for now and catch the aforementioned titles on TCM or via Netflix in the future.

Text ©2009, Film Intuition, LLC; All Rights Reserved. http://www.filmintuition.com

Unauthorized Reproduction or Publication Elsewhere is Strictly Prohibited.