Note: As I received a press version of the collection, which did not contain the exclusive Jerry Lewis approved collectible behind-the-scenes books, I am limiting my review to the films that were included in the Warner Bothers anniversary release including the Blu-ray of The Nutty Professor and the DVDs of Cinderfella and The Errand Boy respectively. Lewis fans will also appreciate that in addition to the exclusive collectible books, the WB edition also offers a bonus CD of "Phoney Phone Calls 1959-1972" that boasts a private selection of prank calls recorded by the man himself.

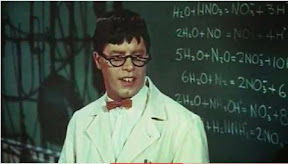

Jerry Lewis is many things but modest is not one of them. According to "The King of Comedy" who played the titular King of Comedy in one of his best performances in Martin Scorsese’s pitch black 1982 comedy, everything about his fan-dubbed masterpiece The Nutty Professor worked.

In fact as Lewis tells us in a behind-the-scenes interview included on the breathtaking high definition 50th anniversary Blu-ray edition of the film that headlines this set, he knew he "had lightning in a bottle."

The problem is in all actuality it works about as well as the chemistry experiment conducted by his accident-prone professor Julius Kelp at the start of the picture – exploding before we even get to the film’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde inspired paradigm that shows the duality of his lead character.

That’s not to say that the film doesn’t have a flash or two of lightning-like brilliance but its most impressive merits are largely due to the cinematic technique of Vertigo special effects man turned cinematographer W. Wallace Kelley and (by borrowing a trick from Vertigo helmer Alfred Hitchcock) in staying on reactions as long as possible before revealing your hand.

Using the cuts of new editor John Woodcock and Lewis’s extensive storyboards, we’re given an admittedly cheesy Frankenstein-like "It’s alive!" fake-out to bluff us with a great moment of misdirection after Kelp first samples the formula he hopes will turn him from a meek zero to an uber macho hero.

Cleverly using the camera to doubles as the point-of-view for our as-yet unseen "new" main character, director Lewis and D.P. Kelley stay on everyone’s reaction while crossing the street to go into a night club. Taking their own sweet time to build overwhelming Hitchcockian horror suspense, minutes go by before they reveal the true identity of Kelp’s Mr. Hyde.

Yet instead of the overt Franken-Beast we’d met moments before, we’re introduced to Lewis’s most subversive portrait of Beauty with the comic actor taking on a dual role as the crass crooner Buddy Love (a Rat Pack style send-up strongly suspected to be modeled on former comedy partner, Dean Martin).

A playboy chauvinist who drinks like a fish, Love gets love much easier than his Jekyll counterpart Kelp who often needs help – once again playing (as the films of Lewis often do) with names, sounds and double meanings like a grown up version of a juvenile knock knock joke.

To this end, it’s worth noting that the woefully misogynistic film (two of three included in the set) that essentially blames women for choosing bad boys over nice guys originally named Kelp’s female love interest Stella Pain.

Much to her credit, the actress Stella Stevens who brought her to life (lovingly captured in ethereal Vertigo like beauty shots throughout) refused to play “a pain” and thus Miss Purdy was born.

For in director/co-scripter Lewis’s eyes women are either pretty or pains. And this idea is reaffirmed by a final gag that undoes the entire point of the film following Kelp’s moving confession at the college prom wherein he outs his experiment and tearfully explains the movie’s moral that you need to love yourself before anyone else can do the same.

Unfortunately Lewis wants love and life three ways – as a boy, a beauty and a beast in a joker’s skin with flashier clothing – as Purdy agrees to be with Kelp before she swipes two bottles of the formula that would bring back the monstrous misogynist we’ve just seen dominate another woman in the form of his changed father and newly submissive mom.

While Nutty is known as his masterpiece musical comedy, in all actuality he did his greatest work as a performer before then. Nonetheless in retrospect, it's his purest cinematic work as a director that plays with classical framing and technical specs that catch the eye while the rest of the film’s overly broad comedy and dated performances grate on the nerves with the same annoyance as nails do on the chalkboard in one unforgettable scene.

Intriguingly as an actor, however, his greatest example of musical comedy evident in the set occurs in the otherwise similarly indulgent, behind-the-scenes solipsistic Hollywood tale The Errand Boy.

One of his better solo efforts following his terrific work alongside Martin, Errand finds Lewis reprising his role as his idiotic alter-ego.

A silent comedy character in a sound era, Lewis’s idiot is railroaded into a position as ineffective studio spy (in place of an efficiency expert) to gather info and report back to the head of the studio who’d plucked him out of obscurity as a sign painter for this very purpose.

A largely plot-free series of gags in the vein of an early Chaplin, Keaton or Lloyd picture, in the film that was also directed by the star (once again illustrating his knack for cinematic storytelling), Lewis does some of his most amazing work to date.

Including an admirably understated yet technically impressive special effect of him swimming underwater while conveying his thoughts on oversized cue cards (like a live action WB cartoon) to two lovely sequences with puppets that catches his childlike sense of wonder and play in the attempt to "put on a show," the film’s ultimate showstopper is a boardroom riff choreographed to Count Basie’s "Blues in Hoss Flat."

Chomping on a phallic cigar and gesturing wildly to perfectly synced beats of the jazz track while pretending to be the big boss, (which Family Guy paid homage to in a thrilling deleted scene you can see below), although he would bring Basie to life again in Cinderfella, it’s here where we see him at his most freewheeling and creative.

The musicality of comedy in Errand Boy is at its strongest and most impressive, which in its own quiet way helps explain perhaps how and why he worked so well with partner Dean Martin (before their legendary messy split) by revealing that they were much more alike and better suited to one another than people think.

Unfortunately, his obsession with wanting to toot his own horn versus the one in Basie’s track gets in his own way once more as Lewis falls back on his passion for sign-posting soliloquies as Errand reaches its climax – letting his detractors have it with both barrels in a speech lauding the talents of actors that damn near likens them to saints.

If you’re able to overlook a few loose ends and a final sequence that reeks of narcissistic delusions of grandeur, Boy is the best example in the box of what Lewis had to offer at the peak of his powers as an performer.

Despite this, of the three titles included, he’s at his most overly musical in the most mainstream feature of the lot via writer/director Frank Tashlin’s misogynistic gender-reversal fairy tale, the coming-of-age musical comedy Cinderfella.

Beautifully lensed by Haskell B. Boggs (who also shot The Bellboy), Cinderfella finds Lewis as the put-upon stepson turned domestic slave Fella to his selfish stepmother and her two snobbish sons.

Motivated by the prospect of earning their affection (a recurring Lewis theme even prior to Buddy Love), Fella lives at their endless beck and call before he’s eventually manipulated by the trio when they realize his well-to-do father hid a special fortune for Fella in an unknown location.

Receiving clues in his dreams where he’s visited by his loving father, the sons hope to tire him out to get the payoff even faster by tricking him into thinking he’s become their temporary friend. But while the grown manchild Fella is visited at night by dreams of his father, during the day he gets the surprise of his life when his own fairy godfather appears just before the family’s expected arrival of the European houseguest, Princess Charming.

Eager to help Fella land the princess in order to “put women in their place” by miserable husbands who’ve been unhappy in marriages to nagging wives who were upset that the erroneous, female written fairytales they read didn’t land each of them their own veritable prince charming, the fairy godfather has been sent to expedite Fella’s happy ending for the “good” of mankind.

Needless to say, it’s easily disturbing in light of not only Lewis’s own misogynistic remarks in 2000 (that women - not even Lucille Ball are funny) as well as the repeatedly disturbing negative treatment of women in this set’s handful of films.

Fortunately of course, you’re able to separate the man from the character and appreciate the pathos and drama of heartbreaking moments in Cinderfella as well as enjoy another Count Basie air-jazz kitchen choreography session.

But ultimately, save for some moments of pure magic and an enviable talent for filmmaking that I believe has gone unappreciated with too much emphasis on his stardom, when viewed back-to-back-to-back – rather than hoping to uplift and entertain – the films seem more driven by solipsism and anger than they do overall by joy.

Don't get me wrong, when the humor hits, it’s electric indeed but far too often the collision of comedic musicality, freewheeling chaos and way too many ideas cause the lightning in Lewis's bottle to simply explode into memorable bits and pieces rather than a cohesive, rhythmic jazz like whole.

Text ©2014, Film Intuition, LLC; All Rights Reserved. http://www.filmintuition.com Unauthorized Reproduction or Publication Elsewhere is Strictly Prohibited and in violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. FTC Disclosure: Per standard professional practice, I may have received a review copy of this title in order to evaluate it for my readers, which had no impact whatsoever on whether or not it received a favorable or unfavorable critique.