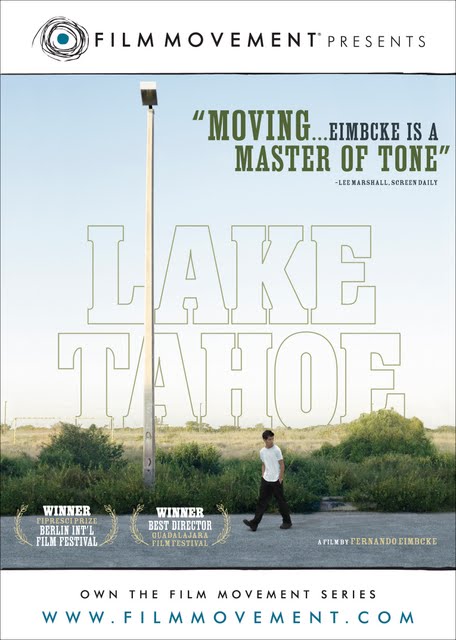

Now Available from Film Movement

Photos

Photos

Join Film Movement

If you were to ask writer/director Fernando Eimbcke, why The Beatles crossed Abbey Road in their most iconic album cover, chances are he wouldn’t say it was only to get to the other side. Much like the four lads from Liverpool as well as the main character he would create in his follow up feature to Duck Season, Eimbcke embarked on an unpredictable journey, which in his case took over two years to travel from "Abbey Road" to what would eventually become Lake Tahoe.

Originally titled “Revolutions Per Minute” to pay homage to the RPM of the "Abbey Road" record for which a young man searches after realizing he’s lost his father’s favorite LP at a party, Eimbcke and co-writer Paula Markovitch ended up incorporating their own personal experience of losing their parents in another draft. Eventually "Revolutions Per Minute" evolved into a contemporary take on Italian Neorealism with the LP replacing the lost transportation in Vittorio De Sica’s heartbreaking classic, Bicycle Thieves aka The Bicycle Thief.

Yet, the record was left on the turntable in the duo’s various writer’s rooms in favor of a more autobiographical and naturalistic spin by teasing its audience initially in our assumption that like De Sica, the film is driven by our hero’s plight to get the car he’d just crashed into a telegraph pole ready to drive once again. And while getting back on the road does seem to be the main goal of Juan (Diego Cataño) as he ventures throughout the wide open spaces of Puerto Progresso, Yucatan looking for an auto repair shop that's open instead of Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City, soon it’s apparent that more than anything, Juan just wants to find distraction from what we later discover is the death of a loved one.

Stripping away the elements until he was left with only what is essential which he likens to his preference for "a well made piece of bread" instead of a "fancy three-layer cake with lots of icing and stuffed with fruits and decorations," Fernando Eimbcke abandoned the "Abbey Road" connection altogether. Although perhaps one of the other reasons for the change could've been basic economics as was evidenced when extra Rolling Stones songs took the place of bonus Beatles tunes in Wes Anderson’s already budget-strapped Royal Tenenbaums years earlier. However, Eimbcke's decision to let the sound of silence become the audio does not go unnoticed.

And this is even eerier when you couple the relative lack of noise with the overwhelmingly bare, wide static shots that were captured in exceedingly long, slightly uncomfortable uninterrupted takes that make us feel as though we were taking in the visual interpretation of-- if not a fugue structured dirge-- than what Babel director Alejandro González Iñárritu described as “a sustained musical note.”

Needless to say, the experimental style of the film that acknowledges its influences literally with a a dog named after De Sica and a relationship he shares in Film Movement's press kit that echoes the Italian's film Umberto D is not one that is sure to appeal to mainstream audiences. Going out of its way not to offer you information or a real natural structure, admittedly it's pretty pretentious all around so much so that although I admired the craftsmanship of what Eimbcke boldly calls "an artisan movie," even I found myself overwhelmingly tested to try and engage with the film, be patient with its sleepwalking presentation, and overall just try to stay awake.

Throughout, he fills the piece with sudden fade-to-black segues which initially I felt were yet another homage before learning they began accidentally. And while there were some genuinely earnest moments of raw emotion and intriguing human connection in Tahoe as Juan meets individuals on his journey, in the end I felt a bit irritated with the morality of the main character to go off on his rambling quest as opposed to be there for his confused, lonely younger brother and fragile mom.

Additionally, when you read Eimbcke's comments that his own cinematic quest was "to make film in the purest state: to put together one image after another and give them all a meaning," you're kind of left scratching your head. Unless years of academic study are wrong, isn't that the way all films-- even ones that don't opt for the label of "artisan movies"-- are supposed to work?

While I do appreciate the autobiographical component, I'm still wondering if we would've been better off with the "Abbey Road" influence and why his journey to a symbolic version of Lake Tahoe had to be achieved through the old cliche of a "willing woman." Because of the movie's enormous potential and sheer cinematographic beauty which does most of the storytelling overall, I'm baffled as to why exactly it took two years and the valuable resource of the Sundance Screenwriters Lab to achieve the final product.

With the repetitive fade-to-blacks, I found myself rewinding the 81 minute work a few times just to ensure I hadn't actually nodded off and missed something vital. It's this problem that impacts the film overall from being anything but a fascinating experiment since essentially Lake Tahoe is a film that perfects its tone but would've been infinitely more effective from a viewer-awareness standpoint if it had been cut into a 30-45 minute "artisan short movie."

2009 DVD Releases from Film Movement

Text ©2009, Film Intuition, LLC; All Rights Reserved. http://www.filmintuition.com

Unauthorized Reproduction or Publication Elsewhere is Strictly Prohibited.

FTC Disclosure: Per standard critical practice, I received a review copy of the film from Film Movement in order to evaluate the work: "Abbey Road" not included nor a map to journey to the real Lake Tahoe.