7/02/2014

Criterion Collection Blu-ray Review: L'eclisse (1962)

Alternate Titles: L'Eclisse; The Eclipse

A film about alienation and the fleeting nature of relationships in director Michelangelo Antonioni’s then contemporary surroundings of Italy in the early 1960s — whether it’s by way of barriers, borders, or character blocking — from the moment L’eclisse begins its characters barely connect on any level.

In fact from its opening sequence which depicts the end of what we perceive to be a long relationship, as the film’s restless heroine (and stand-in for Antonioni) played by Monica Vitti breaks up with her older lover, the two characters are placed in a room only a few feet apart and they can’t bear to look one another in the eye.

In our current era of strict filmic adherence to eye-levels and matched continuity where people view confrontations on the big screen yet avoid the same experience by hiding behind the small screens of their smartphones which are frequently used to end relationships or mask emotion, this messiness — both cinematically as well as interpersonally — is hard for viewers to handle.

Stylistically self-conscious, admittedly stagy, and absolutely unorthodox, the way their eyes fail to hold one another’s gaze made me actually wonder at first glance whether the male character (played by Francisco Rabal) was supposed to blind.

While metaphorically that is likely true, Antonioni is quick to correct this false assumption. He directs Rabal to stand up and walk directly over to Vitti, whom his character later follows home like a lost puppy, uncertain how to dissolve their relationship which by that point had become little more than routine.

A curious decision on Antonioni’s part, the fact that L’eclisse made me question Rabal's sight (even for a split second) actually speaks to the much larger theme of the work which is that in all actuality we don’t really “see” each other.

Whether this is due to apathy, existential angst, a form of self-preservation, or something different altogether is open to interpretation, yet the idea that even when we do use our eyes we never really know what’s going on floats through Antonioni’s work of this period.

Beginning with his most overt exploration of the theme in 1960's L’Avventura, the characters in Antonioni’s cinema are far removed from one another on a number of levels.

This is evidenced in the search for the missing woman in L’Avventura, emotionally in 1961's La Notte and repeatedly in the trilogy as characters are cut off by barriers again and again.

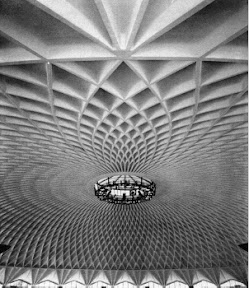

The recurring use of barriers has a much larger meaning as Antonioni's frames employ architectural alienation to create a symbiotic relationship between our immediate environment (namely, an urban landscape) that also ties in with the one we have with one another on a human level.

He takes this idea to its furthest point in L’eclisse, by not only using the techniques and motifs he’d touched upon previously in a stronger way but also adding another layer of ambiguity to the mix.

Gone With the Wind may have been released decades earlier and the song “She’s Like the Wind” wouldn’t be written for a few more decades but in his ’62 film, Antonioni likens the fickle nature of its characters to the wind by making it yet another sensory motif to suggest that we can see each other about as well as we can see the wind.

The lovers in L’eclisse blow through one another’s lives like the fan that’s used at the beginning of the picture and the breeze that comes through the frame and blows the papers near the end of the film after Vitti has tentatively started — and just as quickly stopped — and walked away from yet another relationship.

With characters who would rather kiss "Between the Bars" (again decades before the Elliott Smith song spun this idea into a new direction) or through the use of glass to add a new reflection or layer of reality than the one they're experiencing together, it seems as if the two are only pulled together by the force of their surroundings.

For as soon as they get enough space in between them, the lovers in an Antonioni film are engulfed, overpowered, and therefore threatened to drift apart because there's nothing "real" or metaphorically concrete holding them together than the literal reality of walls or buildings made of concrete.

The third in a thematic trilogy, Antonioni's work is centered on “Eros, art, business, and emotional alienation in the contemporary world,” as Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote in his Criterion essay of the film. L’eclisse explored the filmmaker’s “preoccupation with objects and places overtaking and supplanting people” as Vitti falls into a mismatched meandering romance with Alain Delon’s stockbroker that seems doomed from the start.

It's another “modernist mystery story” that gives Vitti a chance to play a sort of “detective figure” investigating Antonioni’s “troubled inquiries into the shifting appearances of our reality” as Gilberto Perez wrote in his Criterion essay analyzing the director’s collaborations with Vitti. And while L’eclisse is perhaps the most artistically audacious of the three titles, its influence on future generations of filmmakers cannot be understated.

A favorite of Martin Scorsese, who most assuredly would’ve been intrigued by the way that men and women seem to speak two different languages in one of Antonioni's quietest and perhaps most Jacques Tati-like and likewise silent film inspired efforts, there’s a bit of L’eclisse in After Hours as well as Raging Bull, The Aviator, and The Wolf of Wall Street.

Likewise, given the repetition of past locations and the way that previous frames are now charged with meaning when repeated, its experimentally allegorical, poetic and symbolism-drenched ending (which some U.S. distributors actually removed from the film reel because it left out its protagonists completely), L'eclisse has a hypnotic undercurrent we’ve seen throughout the filmography of Wong Kar-wai and Sofia Coppola.

Featuring one of the best and most informative booklets I’ve seen included in a Criterion set in months, this gorgeous restoration and Blu-ray transfer plays particularly well after not only the previous two Antonioni films in the trilogy that captured his thoughts at a certain time and place, but also when viewed with one of the many films it inspired.

Watching it juxtaposed with unexpected titles adds extra layers to the original work while also helping you better appreciate the impact that a film about two people who could barely see one another (let alone their true selves) had on changing the way we saw narrative cinema forever.

Text ©2014, Film Intuition, LLC; All Rights Reserved. http://www.filmintuition.com Unauthorized Reproduction or Publication Elsewhere is Strictly Prohibited and in violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. FTC Disclosure: Per standard professional practice, I may have received a review copy of this title in order to evaluate it for my readers, which had no impact whatsoever on whether or not it received a favorable or unfavorable critique.