6/17/2014

Criterion Collection Blu-ray Review: Red River (1948)

Although he embraced nearly every genre from adventure to Film Noir to screwball comedy throughout his enviable career (and didn’t shy away from blending several together in the span of a single film’s running time), technically speaking, 1948’s Red River was Howard Hawks’ first western.

Admittedly that’s an amazing feat when you consider the film’s overall complexity. Yet as a character driven storyteller less concerned with traditional structure and formula than he was in spinning a memorable yarn, Red River had all the hallmarks of a Hawks classic.

Coming right off the heels of To Have and To Have Not and The Big Sleep — both of which starred Humphrey Bogart — Hawks dared to cast the white-Stetson clad, All-American cowboy hero John Wayne in a role that was decidedly better suited to guy like Bogart whose screen fedoras and Stetsons typically ranged in color from black to gray.

A subversive casting decision, Hawks also aimed to rip that black hat/white hat surface level philosophy to shreds.

While we get the impression The Duke begins the film like the heroic cowboy we’d all come to know and love from movies like Stagecoach, within River's first act Hawks gives audiences their first glimpse of Duke as a Noir tinged antihero after he makes a fatal mistake by not bringing his lady love with him to settle land and build a cattle empire.

Losing her to frontier violence in a (thankfully) offscreen Native American attack, Wayne’s hardened Tom may have lost his beloved but he unexpectedly gains an adoptive son.

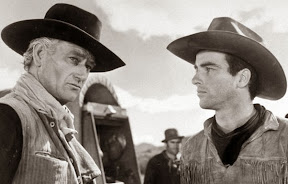

Taking a young boy named Matt under his wing who’d likewise lost everyone he’d had to old western violence as well, Tom becomes the veritable father to the child who grows to become Montgomery Clift.

Jumping ahead in time until the end of the war which found land overtaken by carpetbaggers and all of the money depleted from the south, Tom and Matt decide to go where they can make a living by organizing a late nineteenth century cattle drive from Texas all the way to Missouri along the Chisholm Trail.

A post WWII cinematic study of evolving masculinity across two generations as contrasted by Wayne’s hard-hearted tyrannical patriarch and Clift's sensitive, contemplative, level-headed veteran who’s experienced violence as a survivor and a soldier embodied by the actor in his first screen role, Red River is also another in a long line of father/son, mentor/protégée male “love stories” that would populate Hawks’ career.

Essentially a new variation of an old storyline and/or an unofficial thematic sequel to Only Angels Have Wings which he made a decade earlier and would follow up with again each decade with new screen interpretations such as Rio Bravo in the ‘50s and El Dorado in the ‘60s, Red River was a character-driven western first and foremost.

Distinctly Hawksian with its screwball “three cushion dialogue” that talked around points like characters were shooting pool and aiming for rebounds and style points, in the oeuvre of Hawks, the women served as dialogue-heavy aggressors — articulating things that the men in their lives would never bring themselves to admit like Jean Arthur in Wings, Bacall in Have and Sleep or Angie Dickinson in Bravo.

Thus, following suit, it's a role that the filmmaker’s contracted second choice of Joanne Dru was given in River that she managed to play pretty damn well despite lacking the presence of the other stars (and a rushed ending that even the director concedes just never worked completely right in any way, shape or form when contrasted with the rest of the picture).

And although Hawks was inspired by master western filmmaker John Ford, Red River was the first film that convinced Ford that “the son of a bitch” Wayne could actually act, thereby facilitating the next phase in Duke's evolving role in subversive ‘50s and ‘60s masterpieces like The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

Yet more than just awe-inspiring for what it did for Wayne’s career, it’s also a fascinating historical document to illustrate the change in screen acting.

For not only did River launch newcomer Clift’s career but as such it also inspired a new generation of actors from Marlon Brando to James Dean and Paul Newman to embrace the natural, Stanislavski method as opposed to the demonstrative expressive “show me” technique popularized in the '20s and ‘30s.

While Hawks was the first to discount his skills as a filmmaker by giving credit elsewhere (such as second unit director Arthur Rosson or cinematographer Russell Harlan), or acknowledging the role that luck played in helping him execute an occasional poetic “John Ford shot,” the film is still influential.

Cinematically, this is particularly evident given the way that — much like the friendships that occur throughout his filmography between an older man and a younger one based on their professional camaraderie and ability as fliers, fighters etc. — he liked to rely on his actors’ talents to play things out when it came to his edits.

Cutting on movement rather than action shots to keep edits hidden in order to spotlight the actors so you know that it’s really Walter Brennan driving that wagon across the river, Wayne catching a shotgun and handily firing three times or Clift hopping into the stirrup to get on his saddle, Hawks ensures a sense of realism and masculine cool simultaneously.

Likewise, from a narrative perspective, he preferred to open sequences (and frequently his films) with a fast-paced action-packed moment that gets us right into the story before slowing things down to bring us up to speed with explanations or expositions.

By way of this effect, Hawks once again achieves with his camera the same billiard like rebounds and style points that take a backward way into traditional storytelling, which he frequently utilized with his famous “three cushion dialogue” as he discussed with Peter Bogdanovich in his book Who the Devil Made It.

And knowing him better than most, Bogdanovich makes a welcome appearance as a film scholar on the Criterion set, offering key insights and behind-the-scenes information that makes a great companion to the Hawks chapter of Devil.

Gorgeously restored to a sharp, high definition sheen, The Criterion Collection serves up both definitive versions of Hawks’s adaptation of the Boren Chase novel that the author had shortened into a Saturday Evening Post story which he translated into screenplay form alongside Charles Schnee.

Also including the out-of-print original novel with the impressive dual format edition box set that boasts the film in DVD and Blu-ray for a total of four discs, the collection serves up Hawks’ preferred theatrical edition along with the longer “book version.”

Despite being unauthorized by the filmmaker, the book version that is lacking Walter Brennan’s audible narration boasts an ending that’s closest to the one that the helmer had intended.

Threatened with legal action by the litigious Howard Hughes, who felt like Hawks had repurposed the ending he’d written for Hughes’s The Outlaw before he’d been fired, while there honestly isn’t that much of a difference between the two cuts which due to Dru’s rushed, ineffective delivery Hawks has never actually liked all that much, it’s still interesting to see the two back-to-back.

And while I agree that the tone moves from too deathly serious to too jovial ultimately — as Hawks had always emphasized — the film is less fixated on the girl than it is on the relationship between the two generations of men.

Elevated by the compelling interplay between the leads whose dynamic is analyzed in a fascinating new light in the gender and sexuality focused nonfiction study Masked Men which I read during a film school project that dissected Hawks’ Rio Bravo, Red River is not only of the director’s very favorite films he’s ever made (along with Scarface) but it’s one of my very favorite westerns.

The first genre work that actually opened my eyes to what can be achieved in a western, perhaps Red River is so unique because of its novelty as not only the director’s first western but also Clift’s first film and Wayne’s first challenging role.

And while I'm sure the film was liberating to the actors, it's a distinctly Hawksian achievement all-around.

Without the weight of previous genre efforts impacting his thought process, Hawks was uninhibited and free to let the lessons he’d learned on everything from Bringing Up Baby to Only Angels Have Wings and The Big Sleep inspire him to make his own kind of western.

And that’s precisely what Howard Hawks did in Red River, which finds the filmmaker producing the work on his own — less focused on rules or formula than he was determined to capture a stampede of character, conflict, cattle and celluloid to see exactly what type of cinematic endeavor he could achieve.

Text ©2014, Film Intuition, LLC; All Rights Reserved. http://www.filmintuition.com Unauthorized Reproduction or Publication Elsewhere is Strictly Prohibited and in violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. FTC Disclosure: Per standard professional practice, I may have received a review copy of this title in order to evaluate it for my readers, which had no impact whatsoever on whether or not it received a favorable or unfavorable critique.